Part one of a factual series about the Geology of New Zealand’s Fascinating Island Group – the Marlborough Sound (translated from a report produced by Dr Firouz Vladi, geologist)

The Geology of New Zealand – An Overview

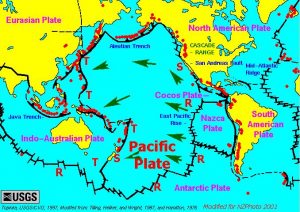

Pacific Plates Overview

The illustration featured to the left shows a contemporary tectonic outline of New Zealand in relation to the continental and oceanic plates and their movement patterns. The science of plate tectonics first emerged during the 1960s. Geologists succeeded in developing a recognized and universally accepted theory about the composition of the earth’s and its movement throughout space and time. New Zealand is a perfect example of the description of the complex and dynamic development processes.

The founder of plate tectonics (initially referred to as continental drift) was the German meteorologist, Alfred Wegener (1880 – 1930), who first published work about the field in 1911.

Alfred Wegener – The Founding Father of Tectonic Theory

The actuogeological model is preceded by a period of development which lasted over several billion years. It has since been possible to trace both the basic principles and the disconcerting elements of this development model right across the world. It is broadly accepted that, approximately 850 million years ago, towards the end of Precambrian Period (the longest spanning geological era), New Zealand and its oldest geological formations were located somewhere between the Rocky Mountains and the Great Lakes on the 20th Parallel North, in what is modern-day Canada. During this time, the continents of the earth were distributed in entirely different positions, forming a supercontinent referred to by geologists as Rodinia. The component parts of Rodinia later broke away from each other before going on to reconfigure themselves in a completely different form (see below), following a movement pattern that conforms entirely to the processes described in the illustration below.

Back to New Zealand – the continental crust has a relatively low-density and therefore “swims” on top of the denser rock formations on the sea floor – the oceanic crust. Low density granite floats on top of the denser / heavier basalt. A glimpse at the graphic below shows that New Zealand effectively forms the eastern edge of the Australian plate. From the point of view of Australia – which is a very stable continental land mass – New Zealand demonstrates countless geological faults – the most significant of which can be found above sea level! Indeed, it is only due to a bulge in the earth’s surface (a direct consequence of a collision between the Australian and Pacific plates), that New Zealand can rise above the ocean at all.

Compared to continental land masses such as Australia or New Guinea, New Zealand boasts a substantial amount of land mass. Much of this land mass is submerged, forming a long, thin continental shelf which is sometimes referred to as Zealandia. The formation of this shelf can – to a large extent – be traced back to the erosion of the Australian and Antarctic massifs – some time before the Tasman Sea and Southern Ocean were formed as a result of the continents drifting apart. This once mountainous region to the east of Australia eroded to form the low-lying hills and erosion products that make up the continental base of New Zealand. The continental shelf has a considerable impact on modern-day New Zealand’s economy. Due to its size, the shelf can support a large amount of fish stocks.

Stay tuned for part two in order to find out more about two of our favourite islands in the Marlborough Sound – Forsyth Island and Pohenui Island